7 Game-Changing Coaching Principles, Part 2: Better Goal Setting, Using Practices To Build Skills, And The Best Way To Confidence Test

++

Many health and fitness coaches unconsciously fall into coaching caricatures: The Hardass, The Cheerleader, The Best Buddy. Not only do these cliches undermine relationships, they hurt the profession. We can do better. And, in this 3-part series, I outline the principles for doing just that. In part 2, strategies for working with clients differently.

++

In part one of this series, I outlined three game-changing principles that’ll change how you view (and interact with) clients. Here they are again:

#1: Become more “client-centered”, less “coach-centered.”

Your client is the world’s #1 expert on his or her own life. Make them an active contributor to their lifestyle plan. And actually value their feedback and thoughts. (At times, more than you value your own).

#2: Ask good questions to practice active, compassionate listening.

Ask great questions and then deeply, actively listen to the answers without any agenda of your own. Become a student of your clients. Listen at least four times as much as you speak.

#3: Focus on what’s awesome, not what’s awful.

Look for areas of your client’s life where they are winning — find how they can apply these skills, experiences, and talents to work through roadblocks and make progress toward a goal that inspires and excites them.

Today, in part two, I’ll share three more, including how to do better at goal setting, how to use practices to build skills, and how to confidence test.

Coaching Principle #4:

Set The Right Kinds of Goals

“What are your health and fitness goals?”

It’s a question asked by professionals all over the world. And it seems like an easy question to answer. Just rattle off how many pounds you want to lose, what pant size you want to wear, what you want your blood sugar numbers to be, or how much you want to deadlift and you’re on your way.

Unfortunately “outcome goals” like these can actively sabotage progress. That’s because they focus us on things that are out of our control while, simultaneously, distracting us from the things we should be thinking about instead: our behaviors (which are within our control).

At Precision Nutrition, we spent decades looking at goal-setting and at how health and fitness coaches set goals with their clients. We concluded that coaches and their clients repeatedly commit the same three errors when it comes to establishing goals.

The good news? It’s relatively easy to turn these “bad” goals into “good” ones. You can do it with this three-step process.

Step 1:

Turn “outcome goals” into “behavior goals”

What are “outcome goals” and “behavior goals”?

An “outcome goal” is something you want to happen, such as losing a certain amount of weight, or running a certain time in a 5K.

A “behavior goal” is an action that you’d do or practice to move toward that outcome, such as putting down your fork between bites, or practicing your running technique three to four times a week.

Why not outcome goals?

While there’s nothing wrong with wanting an outcome like a lower body weight, we often can’t control outcomes because they’re affected by so many outside factors.

Why behavior goals?

Behavior goals, on the other hand, allow us to focus on (and practice) the things we can control—actions, not end results.

What it looks like in practice

A client wants the outcome of “losing twenty pounds.” However, to lose twenty pounds, they’ll have to do certain behaviors like exercise regularly, better control calories, manage stress, and sleep well. So you turn those into goals.

For example, you might spend two weeks with the behavior goal of exercising four times each week for the next two weeks.

Then, another two weeks with the behavior goal of eating slowly and until satisfied, not stuffed.

Then, another two weeks with the behavior goal of taking a five-minute break twice a day to do a mind-body scan.

And another two weeks with the behavior goal of practicing sleep-promoting calm down starting thirty minutes before bed. Notice how the goal is now an action, not an outcome.

Remember

There’s nothing wrong with having a desired outcome. But the outcome is for you, the coach, to think about (and track). Your clients, on the other hand, should be thinking about (and tracking) the behaviors/practices that will lead to that outcome.

Step 2:

Turn “avoid goals” into “approach goals”

What are “avoid goals” and “approach goals”?

An “avoid goal” is something you don’t want—something that pushes you away from your current pain, like “I don’t want to be out of shape” or “I don’t want to be on diabetes medication.”

An “approach goal” is something you do want—something that pulls you toward a better, more inspiring future, like “I want to feel confident and strong” or “I want to live pain free.”

Why not “avoid goals”?

“Avoid goals”—don’t smoke, stop eating junk food—are psycholog- ically counterproductive because telling someone to stop some- thing almost guarantees they’ll keep doing it. In addition, a flat-out “don’t” reinforces the feeling of failure when someone messes up.

Why “approach goals”?

“Approach goals,” on the other hand, give clients something else to do when old habits might have otherwise kicked in. Plus they’re about helping people feel good, successful, and inspired to keep on their journey.

What it looks like in practice

Instead of “no junk food,” try focusing attention on eating more cut-up fruits and vegetables. Instead of “no soda,” try focusing attention on drinking a glass of water with at least three meals each day. Instead of “no stress-eating,” try focusing attention on stress-relieving activities to do instead of eating.

Remember

Writing down a habit you want to stop isn’t enough. The key is to find a replacement your client can lean on when the old habit could kick in. For bonus points, write down why the new action is good for you. For example, “no soda” can be turned into “tea break,” with the following: “Tea is calming, it has antioxidants, and there are lots of flavors I can try. I can even drink it in the mug my daughter made in pottery class.”

Step 3:

Turn “performance goals” into “mastery goals”

What are “performance goals” and “mastery goals”?

“Performance goals” are a lot like outcome goals, but they’re usually associated with external validation—wanting to win a competition for the prize money or wanting to beat a record time. You’re shooting for a specific performance, particularly one that will give you kudos, applause, and/or something good to post on social media.

“Mastery goals” are about learning, skill development, and the intrinsic value of becoming excellent at something, or understanding something deeply.

Why not performance goals?

These have limitations because so many things can influence performance like tough conditions or just feeling bad on race day. They can push you to achieve your best, of course. But they’re demotivating if you don’t achieve them.

Why mastery goals?

Mastery is about the process of continued skill development, which almost always leads to better performance in the long run. Mastery also allows you to focus on the joy of learning, which is gratifying no matter what others think or what time the clock says.

What it looks like in practice

Say your client wants to set a half-marathon personal record. Well, that’s both an outcome and a performance goal. To help them transform it into a mastery goal, you might consider working on running with a smooth, efficient stride and better controlling breathing. This could involve watching video of the client running, identifying technique elements to improve, and turning those into behavior goals.

Remember

Again, you can begin by writing down the performance objective. But don’t stop there. Continue by listing the skills required to help achieve that objective. Then turn those skills into a series of behaviors. This process makes the goal about progression, not performance.

A case study in mastery

I worked with two-division UFC champ Georges St-Pierre for a decade. He’s a case study in mastery. For example, back at UFC 111 in New Jersey, the crowd saw GSP completely dominate his opponent Dan Hardy for five grueling rounds and 25 minutes of fighting.

What the crowd didn’t see was that Georges was dissatisfied. When given the opportunity, he failed to submit his opponent and the fight went to a decision.

Immediately after, at midnight, after a long day and a long fight, while 20 people waited in a private room to take him to a big party in his honor, Georges spent an hour working on submissions with his grappling coach, so he’d get it right next time.

Another example comes from former client Jahvid Best, an elite NFL running back who retired from football and started competing as a sprinter. When asked about his track and field goals, he replied simply: “To master the technique of sprinting.”

He didn’t talk about winning a competition or going to the Olympics. He didn’t even talk about his 100m times. He talked about mastering his craft. And, yes, he did go on to compete at the 2016 Olympics.

If behavior goals, approach goals, and mastery goals are what propel the world’s best athletes, shouldn’t you be using them with your clients too?

Coaching Principle #5:

Establish The Right Practices To Reach Those Goals

When our daughter started gymnastics—at 18 months old—I got the chance to look at coaching in a whole new way. On the one end of the gym were these toddlers in my daughter’s class, with little bodies and big heads, bobbing around, barely able to run in a straight line. On the other end of the gym were the “older girls,” 6- and 7-year-olds doing mind-boggling aerials, flipping around over high bars, and doing crazy stunts on a balance beam.

I became fascinated with the process. How does a good coach take that clumsy toddler and turn her into a graceful gymnast? I decided to find out for myself. I signed up for private lessons with the gym’s head coach and we established a few “outcome goals” for me: Walking handstands and a competent backflip.

However, as mentioned above, “outcome goals” are insufficient on their own. That’s because “do a backflip” isn’t a reasonable instruction. As a coach, you can’t just demonstrate a flip and then tell your athlete to copy you. They’ll surely fail, maybe even get hurt.

That’s why teaching a backflip means breaking the complex movement down into smaller, simpler movements, teaching your athlete those in a logical progression, and then adding them together over time.

So that’s what my coach and I worked on. We broke down handstands and backflips into smaller movement units (skills). Then we came up with specific things I could practice to build up those skills, which would eventually lead me to trying my first walking handstands and backflips.

As I went through my own skill development, I watched our daughter go through hers. They taught her to do back handsprings by starting with 1) back bridges from the floor, then 2) falling into back bridges, then 3) kicking over with one leg from a back bridge, then 4) kicking over with both legs from a back bridge, then 5) doing that with an octagonal tube that guides them smoothly over, and so on until, months later, they got their back handspring. Next, back handsprings on a balance beam.

This idea of progression isn’t unique to sports. The best piano teachers use it to help people eventually play Rachmaninoff. The best yoga teachers use it to help people eventually do inversions. And the best language teachers use it to eventually help people become fluent.

On some level these teachers realize that accomplishing advanced “outcome goals” is never done through heroic single efforts. Rather, “outcome goals” are accomplished through the mastery of a series of basic skills. And those basic skills are accomplished through regular practice.

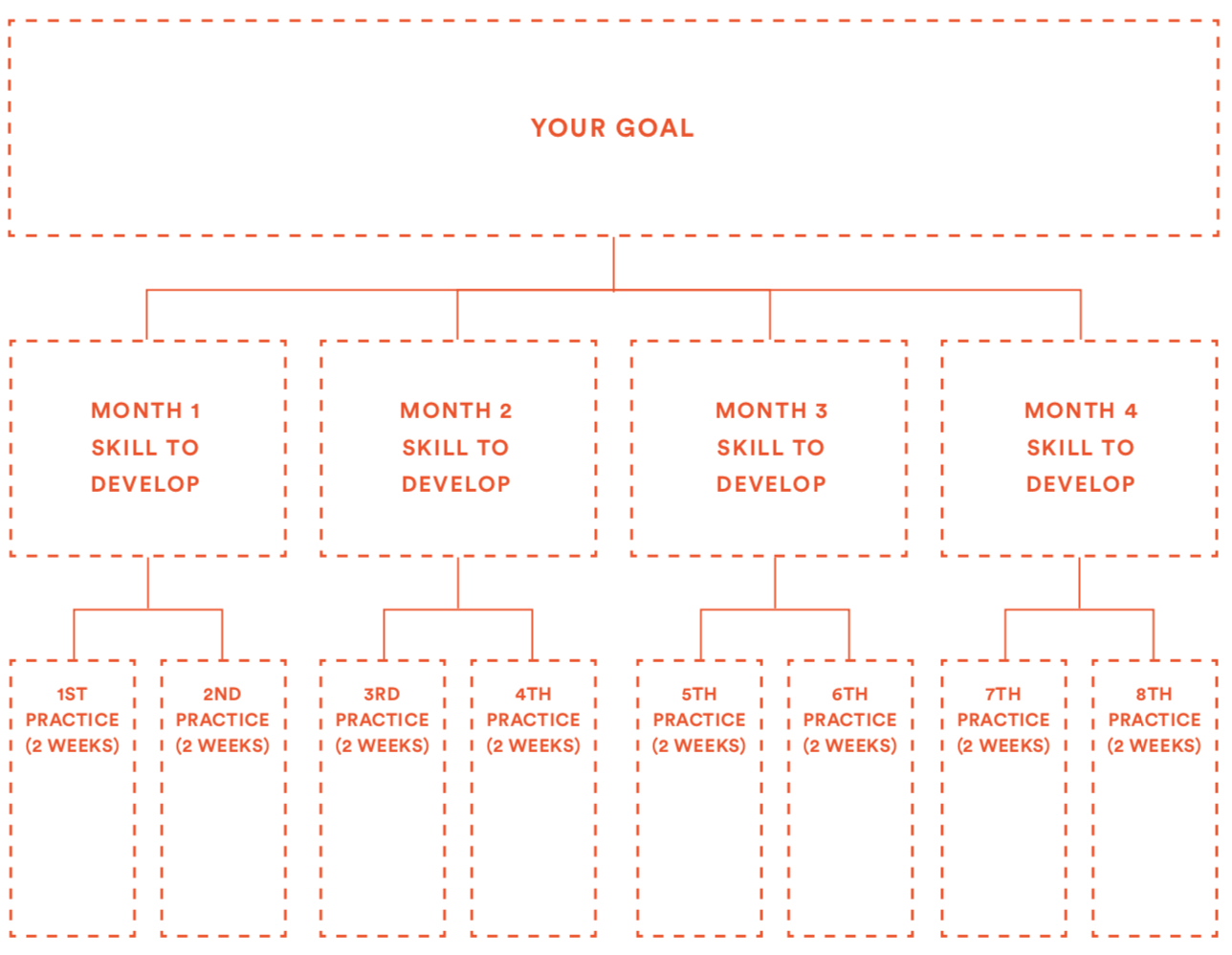

Here’s how I teach coaches and clients to visualize the process.

Let’s now translate this into a common health and fitness example: Weight loss.

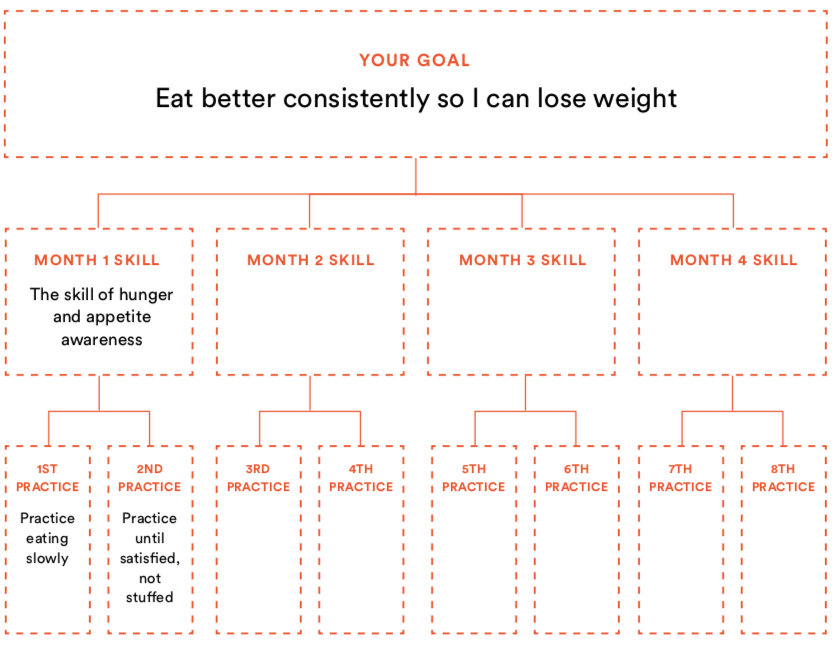

Say a client has an “outcome goal” to lose weight. Sure, write that down on a piece of paper as the desired outcome. But don’t stop there. Your next job is to help them come up with “behavior goals” that’ll help them accomplish the outcome, one of which might be: Eat better consistently.

Eating better consistently is great but it’s still more of a goal than a skill. It’s sorta like the back handspring in that it needs to be broken down into smaller chunks. So you have to ask yourself: Which skills are required to eat better consistently?

At Precision Nutrition we identified that better hunger and appetite awareness is the primary skill for making progress in this area. (There are others, of course. But we always start with this one as it’s fundamental.)

Yet that’s still not totally actionable so we break it down into practices like Eat slowly at each meal (for the first two weeks) and Eat until satisfied instead of stuffed (for the second two weeks). Both naturally lead to better hunger and appetite awareness.

There are also secondary skills, like learning to get back on track when you forget to eat slowly or catch yourself rushing. A related skill involves bringing oneself back to awareness, staying calm, and returning to slow bites, without panicking or getting self-critical.

As you can see, the whole point here is that daily practices (eating slowly at each meal, eating until satisfied instead of stuffed) lead to new skills (better hunger and appetite awareness). New skills are the only way to reach “behavior goals” (eating better consistently). And accomplishing “behavior goals” is the path to producing our desired outcomes (weight loss).

Here’s what that looks like on our worksheet.

This is just one example. The cool part? The practices-skills-goals model can be applied to every area of coaching.

And it’s fairly simple to comprehend. Break goals down into the skills required to accomplish those goals. And break skills down into daily practices that help develop those skills.

To create the best daily practices, you can use Precision Nutrition’s 5S Formula:

Simple: The best practices are small daily actions that can be done in the context of real life. If you ask your client, “On a scale of 0-10, how confident do you feel you could do this practice every day for the next 2 weeks?” the answer should be a 9 or 10. Anything lower and the practice is too challenging or intimidating.

Segmental: Most goals are too big, or complicated, to try for in one go. Most skills are the same way. So break them down into defined and organized segments.

Sequential: Breaking things down into segments is great. But you also have to practice those segments in the right order. If you do “thing 4” before “thing 1” you’re less likely to succeed. So have clients start with thing 1, then do thing 2, then thing 3, and so on. Do the right things in the right order and success is a reliable outcome.

Strategic: Think this process sounds slow? Fact is, if your practices are strategic, the whole process goes quicker. That’s because strategic practice addresses the thing that’s in your way right now. Focus on that one thing—and only that thing—and a difficult process becomes easier and faster.

Supported: Practices work best when they’re supported by some form of teaching, coaching, mentorship, and accountability.

That moment I watched our daughter in gymnastics triggered a whole new area of exploration, to learn about how people learn. What I discovered has completely transformed how I think about coaching (and learning new skills).

It’s even opened up a new world for my own fitness as I started competing in Master’s level track and field after 25 years off.

At nearly 50 years old, if I approached this goal haphazardly, I risked getting hurt, not performing well, not having any fun. So, instead, I followed the practices-skills-goals model. It’s kept me relatively injury-free for five years now, my times are dropping every year, and I’ve even medaled at the Canadian National Championships.

Oh, and as for my back flip? Nailed it.

Coaching Principle #6:

Always Confidence Test

If you had a lifestyle prescription that you knew, with 100 percent certainty, would transform someone’s entire life if they were to follow it for a full 90 days… but you also knew that — even with the best of intentions—they could only follow it for 10 days… would you still offer it?

Really think about that. I bet you’ve been guilty of it at some point in your career, just as I’ve been. We’ve written “perfect” diet or workout or lifestyle plans for people when we knew they’d never be able to follow them.

It’s the dilemma health and fitness professionals face every day. Yet it’s not just health and fitness people who struggle. It’s well-known in medicine that, on average, patients prescribed life-saving medication will take it less than 40 percent of the time.

That’s why, when people talk about clients wanting “a magic pill,” I often joke, “That’s nice, but they wouldn’t even take it half the time.”

There is, however, a surefire way to increase that percentage: Confidence testing.

Before deciding on a course of action or recommendation, simply ask a client: On a scale of 0 to 10 — where zero is “no chance at all” and 10 is “of course, even a trained monkey can do that” — how confident are you that you can do Practice X every day for the next two weeks.

You could even have them use a scale like this to visualize it.

If a client gives you a 9 or a 10, proceed with the practice. If they score an 8 or lower, work with them to “shrink the change.” This means coming up with different practices until they’re confident enough to give you an honest 9 or 10.

Top-down relationships are about instructions. Do these exercises. Eat this food. Take this medication. The outcome of this kind of coaching is predictable: Low compliance. Sure, a few people will do what you say because you act like the boss. Most won’t. And it’s not just because they don’t like being bossed around, but because you never bothered to ask whether they thought they could do it in the first place.

A coach-centered coach thinks: “This practice is easy. My client should have no problem following it.” A client-centered coach thinks: “Once my client and I come up with the next practice that feels right for them, we’ll make sure it’s something they feel confident they can do for a few weeks.”

Even if a practice seems easy to you (Eating only one extra vegetable a day? That’s a joke!) remember that coaching isn’t about you. If all your client can do is muster up the confidence to eat one extra veggie a day, even if it’s just the parsley garnish, so be it.

Having positive experiences with health and fitness—experiences where they don’t feel like a total failure—will lead to more confidence and bigger challenges down the road. Besides, what’s the alternative? Asking them to eat five extra veggies knowing they won’t? And then what? Chastising them for being weak even though you knew they wouldn’t do it in the first place?

Taking on too much is always a problem, for all of us. When I decided to learn to play the guitar, I came up with ambitious practice schedules (an hour a day!) that I’d never be able to follow. And it paralyzed me. I waited for months until “things got less busy” to get started.

Of course, things never got less busy.

That’s when, frustrated, I changed the expectations. I told myself that I had to play just five minutes a day, and I’d do it when I was putting my daughter to sleep for the night because she loves music.

Sure, five minutes a day wouldn’t build my skills at the same rate as an hour a day. But I was doing zero minutes! Surely, five was better than zero, and I was a 9 on the confidence scale that I could do it every day.

The funny thing is that, many nights, once I got the guitar in my hand, I ended up playing for an hour or more.

Don’t we all do this, in some way, in our lives? We get too ambitious in the beginning. Then, when we fall short of those ambitions, we practice “all or nothing thinking.”

We think: “Well, I can’t go to the gym, so I might as well do nothing,” when fifty air-squats and some stretching is better than nothing. We think: “Well, I blew it with this meal, so I might as well eat whatever I want and start over next Monday,” when getting right back on track with the next meal is a better option.

The irony here is that “all or nothing” doesn’t get us “all,” it usually gets us “nothing.” Which is why I like to practice “always something” instead. This means committing to less than I’m capable of on my best day, but something I’m sure I can do on my worst.

When I decided to learn guitar, if I would have confidence tested my one-hour-a-day goal, I would have quickly realized it was too much. And I wouldn’t have spent months “not-starting.” I would have simply adjusted the expectation down until I got a 9 or 10 on the confidence scale and begun the scaled-back practice the very next day.

Key Takeaways

Today’s article— the second in a three-part series—outlines three more coaching principles that’ll change how you work with your clients. Here they are again:

#1: Set the right kinds of goals.

Turn “outcome goals” into “behavior goals,” “avoid goals” into “approach goals”, and “performance goals” into “mastery goals.”

#2: Establish the right practices to reach those goals.

Break goals down into the skills required to accomplish the overarching goal. And break skills down into daily practices that help deliver those skills.

#3: Always confidence-test.

Ensure that the client is at least 90% confident that they can proceed with the desired practice. If they are less confident than this, work to “shrink the change.” This means coming up with different practices until they’re confident enough to proceed.

Stay tuned for part three where I share the final coaching principle, as well as strategies (and scripts) for speaking to clients in a way that makes them more likely (instead of less likely) to change.

In The Meantime, Want To Learn More? Go Deeper?

Then download this FREE sample of my latest book, Change Maker.

Change Maker shares the tips, strategies, and lessons I learned growing Precision Nutrition from a two-person passion project to a 200 million dollar company that’s coached over 200,000 clients, certified over 100,000 professionals, and revolutionized the field of nutrition coaching.

Whether you work as a health coach, strength coach, nutritionist, functional medicine doc, or rehab specialist, Change Maker will help you discover the right direction to take, the fastest way to make progress, and the practical steps required to build the career of your dreams in health and fitness.

The Health and Fitness Industry's Best Career Guide.

Download Chapter 1 of Change Maker, Dr. John Berardi's new book, totally free.The health and fitness industry is huge, competitive, and confusing to navigate. Change Maker helps you make sense of the chaos and lays out a clear roadmap for success. Get the first chapter for free by signing up below.

By signing up, you’ll also get exclusive updates from Change Maker Academy with more great education. Unsubscribe anytime. Contact Us. Privacy Policy.